Bob Dylan, winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature and one of the greatest American songwriters of all time, has effectively used wind as a metaphor in a number of songs he has written, each with its own distinct message. Although it may not have the same poetic cache, it is undeniable that winds of change are also rippling through the regulatory fabric of modern American health care policy. One push for reform is to change the process by which healthcare insurers pre-approve payment for products and services. Depending on one’s point of view, these proposals are either like the “answer” that is “Blowin’ in the Wind” or the “distorted facts” in the Dylan song, “Idiot Wind.” One thing that is indisputable, however, is that the momentum behind this effort is growing.

Health insurers, plans, benefit administrators and other payers of healthcare benefits (collectively, “Payers”) utilize a variety of tools to control healthcare costs. One such measure, prior authorization, also known as precertification and preauthorization (“PA”), is presently the focus of federal and state reform efforts by physicians, nurses, hospitals and other healthcare providers (collectively, “Providers”). The significant number of PA bills introduced in state legislative assemblies during the past few years, pitting powerful industry lobbying forces against one another in state capitals across the country, is just one indicator of the intensity of this debate. This, combined with a 2022 proposal by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) and an unprecedented announcement by one of the largest Payers in the country, are signs that changes in PA requirements are likely on the way.

The Breeze Becomes a Hurricane

Utilization management (“UM”), also known as utilization review,[1] is a broad term used to describe how a Payer manages health care costs using “patient care decision-making through case-by-case assessment of the appropriateness of care prior to its provision.”[2] PA, the most common form of UM,[3] “is a health plan cost-control process by which physicians and other health care providers must obtain advance approval from a health plan before a specific service is delivered to the patient to qualify for payment coverage.”[4] Payers also commonly use concurrent and subsequent reviews of claims to determine whether a service, device, or drug is medically appropriate.[5] Among these prior, current, and post-service reviews, there is little in the way of healthcare products or services that escapes Payer scrutiny. Since the 1980s, Payers in the United States have used PA requirements for medical services and prescription drugs, and the use of this process has become widespread.[6] For example, a recent survey found that 99% of Medicare Advantage enrollees are in plans that require prior authorization for some services.[7]

The American Medical Association (“AMA”) has become a leading proponent of PA reform in the U.S. Going back to at least 2011,[8] the AMA has published numerous PA studies and statements advocating for reform. More recently, the AMA convened a 17 member workgroup composed of state medical associations and national medical specialty societies, provider associations, and patient representatives, to create a set of “best practices” related to PA and other UM requirements.[9] The group subsequently published a list of 21 PA and UM reform principles, based on five broad areas of concern: 1) clinical validity, 2) continuity of care, 3) transparency and fairness, 4) timely access and administrative efficiency, and 5) alternatives and exemptions.[10] For the most part, the principles are not overtly partisan. For example, the first item on the list provides: “Any utilization management program applied to a service, device or drug should be based on accurate and up-to-date clinical criteria and never cost alone.”[11] However, the AMA is not shy about voicing its concerns about the over-use of PA processes, as evidenced by this statement from a 2017 AMA report:

UM requirements often involve very manual, time-consuming processes that can divert valuable and scarce physician resources away from direct patient care. More importantly, PA and other UM methods interfere with patients receiving the optimal treatment selected in consultation with their physicians. At the very least, UM requirements can delay access to needed care; in some cases, the barriers to care imposed by PA and step therapy may lead to the patient receiving less effective therapy, no treatment at all, or even potentially harmful therapies.[12]

As part of its ongoing advocacy efforts, the AMA gathers data measuring the impact of PA requirements on patients and physicians. Results from its 2022 survey of 1,001 practicing physicians include these alarming findings:

- 94% of physicians report care delays as a result of PAs;

- 80% of physicians report that PA can at least sometimes lead to treatment abandonment;

- 31% of physicians reported that PA has led to a serious adverse event for a patient in their care;

- 25% of physicians reported that PA has led to a patient’s hospitalization;

- 19% of physicians reported that PA has led to a life-threatening event or intervention to prevent permanent impairment or damage; and

- 58% of physicians treating patients in the workforce report that prior authorization has interfered with a patient’s ability to perform their job responsibilities.[13]

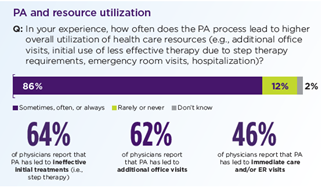

Physicians reported that their practices, on average, complete 45 PAs per week, taking almost two business days each week. And in possibly the most contentious finding of all, a majority of physicians surveyed stated that PA, instead of eliminating unnecessary treatment, had actually increased healthcare utilization:

Payer data about PA processes, particularly data that show PA measures are effective in controlling costs or increasing quality of care, often cited as key reasons they are imposed,[15] is surprisingly hard to find. Consider this statement from a recent report on PA efforts by KFF (formerly the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation), a leading voice on the subject of healthcare policy: “There is little information about how often prior authorization is used and for what treatments, how often authorization is denied, or how reviews affect patient care and costs.”[16] One reason for the dearth of publicly available data is that private Payers, largely, consider their PA data to be proprietary and confidential.[17] A number of state measures and a new proposal by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) include provisions that require reporting of PA statistics.[18]

Not all PA reform efforts have originated solely with Providers. On January 18, 2018, the AMA, American Hospital Association and American Pharmacists Association, together with various Payers, including America’s Health Insurance Plans (“AHIP”), the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association and the Medical Group Management Association, released a “Consensus Statement on Improving the Prior Authorization Process.”[19] The announcement outlines five “opportunities for improvement in prior authorization programs and processes that, once implemented, can achieve meaningful reform.”[20] The five broad areas of agreement are:

- Selective Application of Prior Authorization – includes encouraging the use of PA programs that “selectively implement prior authorization requirements based on stratification of health care providers’ performance and adherence to evidence-based medicine…”.

- Prior Authorization Program Review and Volume Adjustment – regular reviews of “the list of medical services and prescription drugs that are subject to prior authorization requirements [that] can help identify therapies that no longer warrant prior authorization…”.

- Transparency and Communication Regarding Prior Authorization – includes encouraging “transparency and easy accessibility of prior authorization requirements, criteria, rationale, and program changes…”.

- Continuity of Patient Care – although various standards (legal and otherwise) are in place, notes “additional efforts to minimize burdens and patient care disruptions associated with prior authorization should be considered…”; and

- Automation to Improve Transparency and Efficiency.[21]

Collaborative PA reform efforts have also been initiated at the local level. One notable example is the PA working group formed by the Tennessee Medical Association (“TMA”), meeting monthly since July 2020, which includes the TMA’s Insurance Issues Committee chairperson, the assistant Tennessee Insurance Commissioner, major payer medical directors and subject matter experts, practice administrators, a practice consultant, and representatives from the AMA and AHIP.[22] However, despite these and other apparently well-intentioned efforts, no national consensus on PA reform has emerged, leading the AMA in May of 2022, to accuse the health insurer industry of “apathetic or ineffectual follow-through on mutually accepted reforms….”[23]

A Rustling in the Leaves

According to the AMA, a majority of states are presently considering PA reform bills.[24] Significant PA reform legislation has been enacted in a number of states, including Delaware,[25] Ohio,[26] Illinois,[27] Michigan,[28] Vermont,[29] West Virginia[30] and Texas.[31] Mississippi’s legislature also passed PA reform legislation by overwhelming numbers in its 2023 regular session,[32] only to have the bill vetoed by the state’s Governor who claimed it “had the potential to seriously increase the cost of health care in Mississippi.” [33]

The Lone Star state’s 2021 enactment of HB 3459 is especially notable for its so-called “gold card” feature, a “privilege obtained in which a physician or provider is not subject to a preauthorization requirement that otherwise applies with respect to a particular health care service.”[34] A physician or other provider qualifies under the Gold Card legislation for a particular health care service if the insurer “has approved or would have approved not less than 90 percent” of PA claims during the most recent six-month evaluation period.[35] Physicians and providers can be reevaluated by insurers in six-month increments and can lose their exemption if a random sample of claims reveals that less than 90% of claims would have failed to gain approval by the insurer.[36]

One factor that hinders comprehensive PA reform in the U.S. is a fragmented and complicated approach to the regulation of Payers and healthcare. Since the passage of the McCarran-Ferguson Act in 1945, the regulation of the “business of insurance” (an undefined term in the act) has been relegated to the states.[37] This does not mean, however, that the states have carte blanche to enact PA reforms. Probably the single largest obstacle to state reform efforts is the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA), which preempts “any and all State laws insofar as they … relate to any employee benefit plan” governed by ERISA.[38] Where the preemption line should be drawn is a fact-specific, often-litigated area of the law.[39]

A similar issue that state legislators face when designing PA legislation is whether to include Medicaid and its closely related cousin, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), programs that are regulated at both the state and federal levels. Indeed, state reformers have not been consistent in their approach to these programs. For example, Texas legislators opted not to include Medicaid in their Gold Card legislation,[40] while the Illinois PA reform bill, passed in 2021, does cover these programs.[41] Excluding ERISA plans and Medicaid drastically reduces the reach of a state’s PA reforms. The Texas Medical Association estimates that the Texas Gold Card legislation will only reach about 20% of Texans.[42]

Feds Catch the Wind

In December of 2022, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (“CMS”) issued a proposed rule designed to address access by Providers and patients to health information and to “streamline” PA processes for Medicare Advantage organizations, state Medicaid and CHIP agencies, Medicaid managed care plans, CHIP managed care entities, and Qualified Health Plan issuers on Federally-facilitated exchanges. [43] These regulations, as proposed, have a number of PA reform features, including:

- PA requirements, documentation, and decisions must be documented through a data exchange that automates the process for Providers to determine: (1) whether a PA is required; (2) identify PA information and documentation requirements; and (3) facilitate the exchange of PA requests and decisions from electronic health records;

- Specific reason(s) for denial of a PA request must be included by Payers;

- PA decisions must be made within 72 hours for expedited (i.e., urgent) requests and within seven (7) calendar days for standard PA requests; and

- PA metrics must be publicly reported by posting them directly on the Payer’s website or via publicly accessible hyperlinks on an annual basis.[44]

If the new rules become law, they would take effect January 1, 2026, with the initial metrics to be reported by Payers beginning March 31, 2026. It is worth noting, however, that this is not CMS’s first attempt at PA reform. An earlier proposal, published in December of 2020, was formally withdrawn in favor of the latest proposal. [45]

You Don’t Need a Weatherman

Just as these and other PA reform efforts reached a crescendo, in probably the most telling development of all, the country’s largest private Payer, United Healthcare, announced on March 29, 2023, that beginning later in the year the company would eliminate “nearly 20% of current prior authorizations” and, beginning in 2024, it would implement a “national Gold Card Program” for certain Providers, “eliminating prior authorization requirements for most procedures.”[46] While the corporate intentions behind such a monumental announcement can only be speculated upon, one thing is certain: federal, state, and private reform efforts are coming together like never before to change America’s extensive healthcare PA procedures. After all, as the bard of Minnesota might say, sometimes “You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the winds blow.”[47]

[1] A. Giardino, R. Wadhw, Utilization Management, StatPearls Publishing (Updated July 11, 2022), available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560806/.

[2] Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Utilization Management by Third Parties; B. H. Gray and M. J., Field, editors; Controlling Costs and Changing Patient Care? The Role of Utilization Management; National Academies Press (US) (1989), at 1, Utilization Management: Introduction and Definitions.

[3] A. Turner, G. Miller, and S. Clark, Impacts of Prior Authorization on Healthcare Costs and Quality, A Review of the Evidence, Center for Value in Health Care (November 2019) 1, Use of Prior Authorization, https://www.nihcr.org/analysis/impacts-of-prior-authorization-on-health-care-costs-and-quality/.

[4] Prior Authorization Practice Resources, American Medical Association (May 18, 2023), https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/sustainability/prior-authorization-practice-resources (last viewed June 10, 2023).

[5] See id. at 1.

[6] A. Schwartz, T. Brennan, D. Verbrugge, and J. Newhouse, Measuring the Scope of Prior Authorization Policies: Applying Private Insurer Rules to Medicare Part B, JAMA Health Forum (May 2021), https://doi.org/10.1001%2Fjamahealthforum.2021.0859.

[7] J. Fuglestein Biniek and N. Sroczynski, Over 35 Million Prior Authorization Requests Were Submitted to Medicare Advantage Plans in 2021, KFF (February 2, 2023), https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/over-35-million-prior-authorization-requests-were-submitted-to-medicare-advantage-plans-in-2021/.

[8] Standardization of Prior Authorization Process for Medical Services White Paper, Prior Authorization: Current Status Described, AMA Private Sector Advocacy, June 2011 (available at AMA Ed Hub, https://cdn.edhub.ama-assn.org>steps-forward) (last viewed June 10, 2023).

[9] See id. at 3.

[10] Prior Authorization and Utilization Management Reform Principles, American Medical Association, et al., https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/prior-authorization/prior-authorization-reform-initiatives#:~:text=Prior%20authorization%20reform%20principles,-An%20AMA%2Dconvened&text=Clinical%20validity,Timely%20access%20and%20administrative%20efficiency) (last viewed June 10, 2023).

[11] Id. at Principle #1.

[12] Report 8 of the Council on Medical Service (A-17), Prior Authorization and Utilization Management Reform, Background (available at https://www.ama-assn.org/media/19571/download) (last viewed June 10, 2023).

[13] See 2022 AMA Prior Authorization (PA) Physician Survey, https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2021-05/prior-authorization-reform-progress-update.pdf (last viewed June 10, 2023); see also Press Release, Toll From Prior Authorization Exceeds Alleged Benefits, Say Physicians, American Medical Association, March 13, 2023, https://www.ama-assn.org/press-center/press-releases/toll-prior-authorization-exceeds-alleged-benefits-say-physicians (last viewed June 10, 2023).

[14] Id.

[15] See K. Pestaina K and K. Pollitz, Examining Prior Authorization in Health Insurance, KFF, May 20, 2022, https://www.kff.org/policy-watch/examining-prior-authorization-in-health-insurance/ (last viewed June 28, 2023).

[16] Id.

[17] See id at 6 (use of “proprietary authorization data from a large Medicare Advantage insurer, Aetna.”) (cited data source: G. Jacobson, et al. “Medicare Advantage 2017 Spotlight: Enrollment Market Update” KFF, June 6, 2017), https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-advantage-2017-spotlight-enrollment-market-update/ (last viewed June 28, 2023).

[18] See, e.g., Press Release, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, CMS Proposes Rule to Expand Access to Health Information and Improve the Prior Authorization Process (December 6, 2022) (available at https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-proposes-rule-expand-access-health-information-and-improve-prior-authorization-process).

[19] American Hospital Association, et al., Consensus Statement on Improving the Prior Authorization Process (June 1, 2018), https://www.ahip.org/resources/2018-prior-authorization-consensus-statement (last viewed June 10, 2023).

[20] Id. at 1.

[21] Id. at 1-4.

[22] Tennessee Medical Association, TMA’s Prior Authorization Workgroup (available at https://www.tnmed.org/prior-authorization/) (last viewed June 10, 2023).

[23] Press Release, American Medical Association, Health Insurance Industry Continues to Falter on Prior Authorization Reform (May 24, 2022), https://www.ama-assn.org/press-center/press-releases/health-insurance-industry-continues-falter-prior-authorization-reform) (last viewed June 10, 2023).

[24] K. O’Reilly, Bills in 30 States Show Momentum to Fix Prior Authorization (May 10, 2023), K. O’Reilly, Bills in 30 States Show Momentum to Fix Prior Authorization (May 10, 2023) (last viewed June 28, 2023).

[25] Del. Code Ann. tit. 18, ch. 33 (HB 381, 148th General Assembly).

[26] Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 3923.041(SB 129, 131st General Assembly).

[27] 215 Ill. Comp. Stat. 200/1 (HB 0711, 2021).

[28] 2022 Mich. Pub. Acts 60 (SB 247, 2022).

[29] Act 140 of 2020 (HB 960) (pilot program).

[30] W. Va. Code §§ 33-15-4s, et seq. (HB 2352, 2019).

[31] HB 3459 (2021 Session).

[32] SB 2622 (2022 Regular Session).

[33] Press Release, Governor Tate Reeves, Governor Vetoes Two Bills That Would Increase Health Care Costs in Mississippi (March 15, 2023), https://mailchi.mp/3eddaa07f493/governor-tate-reeves-vetoes?e=ae3824fee2) (last viewed June 28, 2023).

[34] TMA Frequently Asked Questions on Texas’ ‘Gold-Carding’ Preauthorization Exemption Law and Rules, Texas Medical Association (October 17, 2022) (available at https://www.texmed.org/GoldCardWhitePaper/ (last viewed June 10, 2023); see also Texas Insurance Code Ann. § 4201.651, et seq.; see also 28 Texas Admin. Code § 19.1730, et seq.

[35] Texas Insurance Code Ann. § 4201.653(a).

[36] Texas Insurance Code Ann. § 4201.655(a); see also 28 Texas Admin. Code § 19.1730(2).

[37] McCarran-Fergusson Act of 1945, ch. 20, § 1, 59 Stat. 33 (codified as amended at 15 U.S.C. § 1011 (2018)).

[39] See, e.g., Louisiana Health Service & Indemnity Co. v. Rapides Healthcare System, 461 F.3d 529 (5th Cir. 2006) (Louisiana assignment statute held not to have impermissible connection with ERISA plans).

[40] 28 Texas Admin. Code § 4201.652 (Applicability of Subchapter).

[41] 215 ILCS 200/10 (Applicability; scope).

[42] TMA Frequently Asked Questions on Texas’ ‘Gold-Carding’ Preauthorization Exemption Law and Rules, TMA Office of the General Counsel (October 17, 2022), (available at https://www.texmed.org/GoldCardWhitePaper).

[43] Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Advancing Interoperability and Improving Prior Authorization Processes Proposed Rule CMS-0057-P: Fact Sheet (December 6, 2022), https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/advancing-interoperability-and-improving-prior-authorization-processes-proposed-rule-cms-0057-p-fact) (last viewed June 28, 2023); see also Medicare and Medicaid Programs Proposed Changes, 87 Fed. Reg. 76238 (proposed December 13, 2022).

[44] Id. (CMS Fact Sheet at 3-4).

[45] 87 Fed. Reg. at 76239 (Background and Summary of Provisions).

[46] Easing the Prior Authorization Journey, UnitedHealthcare (March 29, 2023), https://newsroom.uhc.com/experience/easing-prior-authorizations.html) (last viewed June 28, 2023).

[47] Bob Dylan, Subterranean Homesick Blues, from Bringing It All Back Home (Columbia 1965).

Finis